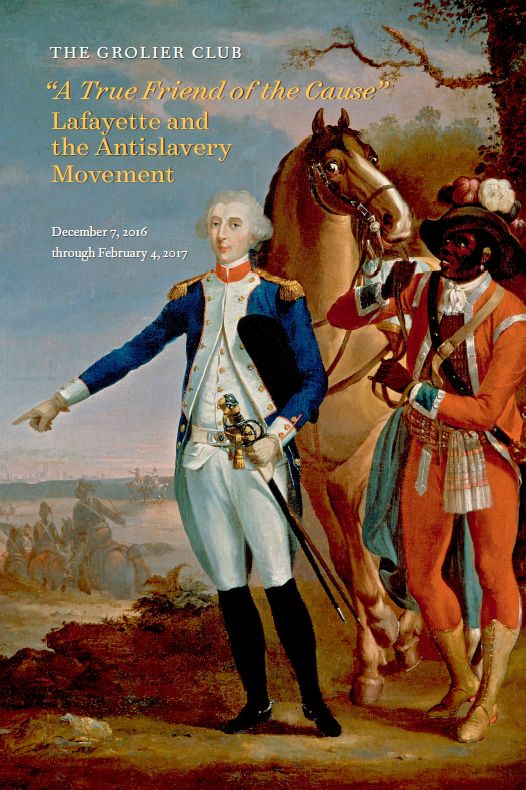

“A True Friend of the Cause”: Lafayette and the Antislavery Movement

The Grolier Club, New York City

7 December 2016–4 February 2017

“I would never have drawn my sword in the cause of America if I could have conceived that thereby I was founding a land of slavery!” The placard featuring this statement in bold, black letters catches the eye of the visitor immediately upon entering the first floor gallery of the Grolier Club. First attributed to the Marquis de Lafayette in 1845, the statement “took on a life of its own in the abolitionist movement and was often quoted,” for instance in African-American historian William Cooper Nell’s The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855), a copy of which is displayed in the same showcase. While Lafayette’s involvement in the American Revolution has been extensively documented, his role as an ardent abolitionist has received little attention. With over 100 items drawn from the collections of Lafayette College, Cornell University, and the New-York Historical Society, this excellent exhibition curated by Olga Anna Duhl and Diane Windham Shaw successfully addresses the various ways in which “America’s Favorite Fighting Frenchman” contributed in spreading antislavery ideas in the young republic and beyond. It is divided into 10 sections, from Lafayette’s first encounters with enslaved men and women in 1777 to his experiment in gradual emancipation in French Guiana between 1785 and 1792 – he acquired properties in Cayenne on which slaves were paid for their labor – and his “Farewell Tour” of the United States in 1824-1825, during which he was feted by free and enslaved African-Americans alike. The rare books, manuscripts, and prints on display show how Lafayette’s efforts were part of a broader transnational movement for emancipation that connected France, Great Britain, and the United States: copies of British abolitionists Granville Sharp’s and Thomas Clarkson’s writings were mailed from one country to another, letters exchanged between Lafayette and fellow antislavery advocates overseas (Benjamin Franklin, Frances Wright, Lucy Townsend), mottoes translated from English into French. The image of the supplicant slave asking “Am I Not and a Brother?”, first introduced in the form of a medallion by British ceramicist Josiah Wedgwood in the late eighteenth century, was soon after adopted as the emblem of the Société des Amis des Noirs with the motto “Ne suis-je pas ton frère?”; it appears here on the title page of Adresse à l’Assemblée nationale, pour l’abolition de la traite des Noirs (1790).

Also emphasized are Lafayette’s direct interactions with African-Americans. Ex-slave James Armistead won his freedom from the Virginia General Assembly in 1787 after obtaining a testimonial from Lafayette – a broadside featuring a facsimile of the text is included in the exhibition – praising his service during the American Revolutionary War; Armistead later adopted the surname Lafayette. The same year the broadside was created, 1824, Lafayette visited the African Free School in New York City. Star pupil James McCune Smith, soon to become a leading abolitionist and the first African-American to receive a medical degree, delivered a welcoming address in front of 450 other students. “In behalf of myself and fellow-schoolmates,” the document reads, “may I be permitted to express our sincere and respectful gratitude to you for the condescension you have manifested this day in visiting this institution, which is one of the noblest specimens of New York philanthropy.” The original copy of the address and other items in the exhibition reveal Lafayette’s enduring commitment to antislavery as well as some of his ambiguities. Lafayette’s relations to blacks were always tinged with white paternalism. With his failed Cayenne experiment, “Lafayette opted paradoxically,” art historian Laura Auricchio points out, “to demonstrate the benefits of gradual emancipation by becoming a slaveholder himself.” He later endorsed the American Colonization Society’s controversial plan to remove free blacks and emancipated slaves to Africa and elsewhere (in an 1826 letter, he suggested Mexico as a place for resettlement); at the same time that William Lloyd Garrison was calling colonization “the most compendious and the best adapted scheme to uphold the slave system that human ingenuity can invent” (The Liberator, November 19, 1831), the American Colonization Society printed 10,000 copies of a broadside reproducing letters of support by James Madison, John Marshall, and Lafayette. After Lafayette died in 1834, however, his name became virtually synonymous with emancipation, even among the most radical black and white abolitionists. Wendell Phillips, who served as president of the American Anti-Slavery Society after the Civil War, liked inscribing Lafayette’s “I would never have drawn my sword” quotation, then signing Lafayette’s name alongside his own, as shown in the last section of the exhibition. As for the placard mentioned above, it was used at the service marking the execution of John Brown, for whom nothing less than armed insurrection would lead to the overthrow of slavery. Lafayette may not have lived to see either France or the United States outlaw slavery, but he remained a source of inspiration for the generations of abolitionists who witnessed the demise of the institution.

Michaël Roy

Université Paris Nanterre